|

The position and

types of text included on a gendai print were also different. First, text

was written horizontally in the lower print border (prints 87-90) instead

of vertically in the side borders or in the picture area. Second, the

artistís name was written most often (93%a) in the roman

alphabet (prints 87, 89, 90) instead of the Japanese syllabary (print 88). Third,

prints were usually (80%) given a title which was written in either the

Japanese (70%) syllabary (prints 88, 90) or the Roman (10%) alphabet. Fourth,

the year in which a print was made appeared on about half (51%) of the

prints (print 90). Fifth, two additional numbers, separated by a diagonal

line, appeared on most (85%) prints (prints 87, 88, 90). The number below

the diagonal line was the total number of copies made of the printb

and the number above the diagonal was the number assigned to a particular

copy of the print.

The publisherís

logo which appeared on some shin hanga and ukiyo-e prints was absent from

gendai prints because the latter were published by the artistc.

Very few gendai artists (2%) added a poem to their prints (print 89).

Finally, more gendai bird prints had a white border (99%) than either

ukiyo-e (7%) or shin hanga (60%) bird prints. These changes reflected the

ever increasing influence of western art practices on Japanese bird

printmakers.†††††

a†† Percentages are based a sample of 2410

gendai bird prints by 1018 artists.Their names, signatures and examples of their work are included in Appendix 3a and Appendix 3b.

b†† Prints with a fixed number of copies are

often called limited-edition prints.

c†† The production of ukiyo-e and shin hanga

prints involved four people; first the artist who designed the print,

second the person who carved the artistís design onto a block of wood,

third the person who added ink to the block and printed the design on

paper, and fourth the publisher who financed print production and marketed

finished prints. Gendai artists took control of all steps in the

printmaking process to maximize the opportunity for self-expression and

creativity at each step.† †††

Picture Composition

The composition of a

gendai bird print tended to be simpler and (or) less realistic than that of

either a shin hanga or ukiyo-e bird print. This tendency likely reflected

the influence of western abstract and (or) surrealistic art on gendai

artists. Birds were unaccompanied in more gendai bird prints (14%) than

either shin hanga (4%) or ukiyo-e (0.5%) bird prints. In print 91 the

picture area was filled by a single, abstract owl and in print 92 by

multiple birds with simplified shapes.†††

|

91†† Unidentified owl (Family Strigidae) by

Minoru Yokota, 190 mm x 250 mm, intaglio print

|

|

92†† Cormorant (Phalacrocorax sp.) and

crane (Grus sp.) by Yō Sugano, 180 mm x 225 mm, intaglio

print entitled ancient birds

|

Plants appeared in far fewer gendai bird prints

(51%) than in either shin hanga (86%) or ukiyo-e (88%) bird prints. The

decline in the number of flower-and-bird pictures is particularly striking

(i.e., 18% of gendai prints versus 53% of shin hanga prints and 66% of

ukiyo-e prints). Even when flowers were included in a gendai bird print

they were often relegated to the background as in print 93. For most gendai

artists, traditional Chinese and Japanese bird-and-flower art in which

flowers and birds were equally important was no longer an influence.

†††† ††

|

|

93†† Long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus)

by Tadashi Ikai, 440 mm x 300 mm, intaglio print entitled flower field

|

|

Gendai artists

also simplified plant shape. For example, only the flower petals of

plants were shown in print 93 and the tall grasses in print 94 had no

leaves.†

|

|

94†† Common snipe (Gallinago gallinago)

by Sadao Satō, 410 mm x 340 mm, screenprint entitled a snipe

|

|

Inanimate objects

such as water and rock also appeared in fewer gendai bird prints (18%) than

in either shin hanga (27%) or ukiyo-e (28%) bird prints. When they were

included their depiction could be more surrealistic than true-to-life. In

print 95 the true effect of reflected light on the color of water was

exaggerated by using shades of color that ranged from white to dark blue.

In print 96 a landscape of conical shapes was created that has no earthly

equivalent and is more likely to be seen when we have our eyes closed

(i.e., dreaming).††

|

|

95†† Little egret (Egretta garzetta) by

Teruhiko Kondo, 400 mm x 305 mm, intaglio print entitled little egret

|

|

|

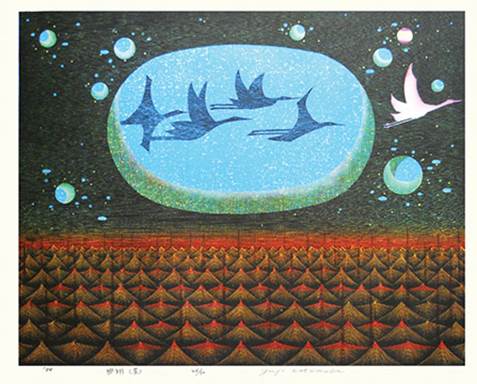

96†† Crane (Grus sp.) by Yūji

Watanabe, 715 mm x 575 mm, woodblock print entitled flying (star)

|

Precipitation appeared much less often in gendai

bird prints (3%) than in either shin hanga (23%) or ukiyo-e (17%) bird

prints. Its infrequent appearance is surprising because some of the most

visually stunning gendai bird prints are those in which it is raining or

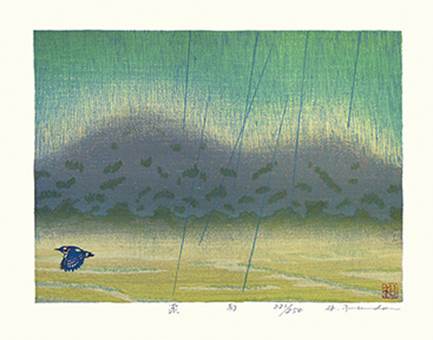

snowing. In print 97 rain helped to create the illusion of

three-dimensional space in a two-dimensional picture. Both the rain and

bird in the foreground are in focus while mountains in the background are fuzzy

as if being partly hidden by the rain. In print 98 the shapes of all

objects are indistinct, as we would see them when our vision was being

hampered by falling snow.

|

|

97†† Greater-spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos

major) by Hirokazu Fukuda, 325 mm x 250 mm, woodblock print entitled

gentle rain

|

|

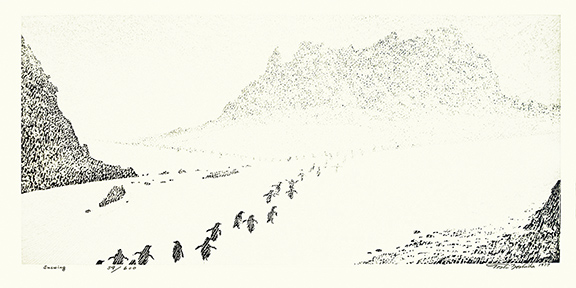

98†† Penguin (Family Spheniscidae) by

Tōshi Yoshida, 640 mm x 305 mm, woodblock print entitled snowing

|

The sun and moon appeared more often but were

drawn less realistically in gendai bird prints (17%) than in either shin

hanga (7%) or ukiyo-e (8%) bird prints. In gendai prints the sun was often

multicolored (print 99) instead of its true red or yellow and the size of

both the sun (print 101) and moon (print 100) were exaggerated. Gendai

artists were the first to include stars (print 100) in bird prints.††

|

|

99†† Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by

Nobuyoshi Koga, 140 mm x 200 mm, screenprint entitled greeting of love

|

|

|

|

|

100†† Scops owl (Otus sp.) by Makiko

Hattori, 190 mm x 240 mm, intaglio print entitled moonlight owl

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

†††† Man-made objects

accompanied birds in about the same percentage of gendai (7%), shin hanga

(5%) and ukiyo-e (5%) bird prints. However, the types of objects

differed. Modern inventions such as the power transmission tower (print

101) only appeared in gendai prints. The scene in print 101 was

relatively realistic compared to others in gendai prints that contained

man-made objects. For example, in print 102 exotic South American birds

were paired with a globe and the concorde jet whose nose cone included a

sharp pencil. In print 103 a collage of unrelated objects appeared behind

a pair of soaring seabirds. The novelty of these surreal scenes makes

them entertaining but also challenging to understand fully.

|

|

101†† Green pheasant (Phasianus versicolor)

by Fumiaki Mutō, 420 mm x 570 mm, digital print entitled pine and

green pheasant

|

|

102†† Four unidentified species of South

American birds by Gō Yayanagi, 450 mm x 455 mm, screenprint

|

|

103 Short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria

albatrus) by Kōsuke Kimura, 400 mm x 440 mm, lithograph entitled

flight - H

|

|

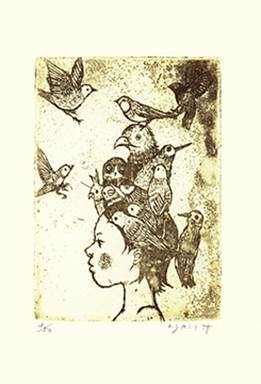

†††† Birds were paired

with humans in more gendai bird prints (6%) than in either shin hanga

(0.1%) or ukiyo-e (3%) bird prints. This pairing took one of three forms.

In the most popular form either a single bird or more than one bird sat

on the head of a human, usually a young girl as in print 104. Less

frequently humans and birds stood side by side (print 105). Finally, in

rare cases a bird was shown impersonating a human as in print 106. None

of the birds depicted in these prints were symbolically associated with

humans in Japan so presumably gendai artists were simply being creative.

The diverse group of bird species shown in print 104 would never be found

together, even in the absence of humans. It is also unlikely that the

mountain climber shown in print 105 could get that close to the wary rock

ptarmigan. To make the connection between the dodo bird and Sherlock

Holmes in print 106 requires help from the artist.

|

|

104†† Multiple species of unidentified birds

by Shiho Murakami, 100 mm x 150 mm, intaglio print

|

|

105†† Rock ptarmigan (Lagopus muta) by

Umetarō Azechi, 125 mm x 110 mm, woodblock print††

|

|

106†† Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) by

Hideshi Yoshida, 150 mm x 150 mm, wood engraved print entitled Sherlock

Dodo

|

Bird Species Chosen

for Depiction

Gendai artists chose a

wide rangea of bird species to depict. Their most popular

choices, shown below, belonged to the following five bird families: (1)

owls (34%b), (2) geese and swans (23%), (3) fowl (22%), (4)

cranes (16%) and (5) doves (13%). Three of these families (i.e., geese and

swans, fowl, cranes) were also among the top five families chosen by both

shin hanga and ukiyo-e artists. The other two families (i.e., owls and

doves) replaced sparrows and egrets plus herons chosen by shin hanga

artists and sparrows and hawks plus falcons chosen by ukiyo-e artists. The

extreme popularity of owls with gendai artists is very surprising for two

reasons. First, owls are not well known by most people because they are

active at night instead of during the day when they hide from view. Second,

until recently owls have had a negative symbolic association (i.e., with

ingratitudec). Today in Japan owls are associated with good luckd

and protection from hardship which may explain why they now appear more

often in Japanese art. The popularity of doves is less surprising. They are

common in both urban and suburban settings throughout Japan and they have a

positive rather than negative symbolic association (i.e., messenger of the

peace god in Japanese mythology).†

a†† 162 species from 66 families were depicted

in the 2410 gendai bird prints examined.

b†† percentage of gendai artists whose chose

a bird from a particular family

c†† The association of owls with ingratitude

is based on the false far-eastern belief that young owls will kill and eat

their parents.

d††† Since the 1950s owls have been

considered to be symbols of good luck and protection from hardship. These

associations are based on similarities between a Japanese name for owls

(i.e., fukurō) and the words for luck (fuku) and no (fu) hardship (kurō).

(1) Owls (Strigidae)

Scops owls (print 107)

and the Ural owl (print 108) were depicted most often. Both are native to

Japan. Scops owls are found in a wide range of habitats, including urban

parks and gardens, while the Ural owl is more common in rural woodland.

|

107†† Scops owl (Otus sp.) by Hiroko

Yamada, 300 mm x 240 mm, intaglio print entitled hunting

|

|

108†† Ural owl (Strix uralensis) by

Takashi Hirose, 150 mm x 200 mm, intaglio print entitled Ural owl

|

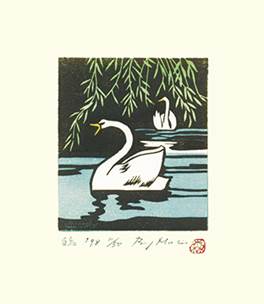

(2) Geese and Swans

(Anatidae)

Captive swans, imported

originally from Europe (print 109), and domestic geese (print 110) were

depicted most often by gendai artists. The wild geese and ducks depicted so

often in both shin hanga and ukiyo-e bird prints were comparatively rare in

gendai bird prints. This substitution of tame waterfowl for their wild

counterparts in gendai prints suggests that gendai artists were more

familiar with waterfowl found in man-made habitats. Understandably, they

had fewer opportunities to view wild birds than their predecessors due to

the continuing process of habitat conversion from wild to man-made.

|

109†† Mute swan (Cygnus olor) by Ray

Morimura, 140 mm x 160 mm, woodblock print entitled swan

|

|

110†† Domestic goose (Anser cygnoides)

by Kotarō Yoshioka, 245 mm x 275 mm, screenprint entitled family

|

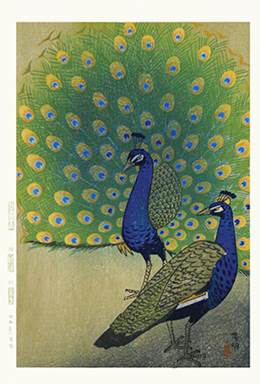

(3) Fowl (Phasianidae)

|

Captive peafowl (print

111) and domestic fowl (print 112a) appeared often in gendai

bird prints. Presumably the colorful plumage of these birds made them

popular choices, just as they had been for shin hanga and ukiyo-e

artists. The latter also depicted colorful, wild pheasants but gendai

artists rarely drew these pheasants. Perhaps gendai artists were simply

less familiar with wild pheasants whose numbers continue to decline due

to the combined effects of habitat conversion for human use and huntingb.††††††††

a†† To enhance the illusion of a domestic

fowl running rapidly the artist exaggerated the length of its neck and

body. It is the same species drawn more accurately in print 81.

b†† Brazil (1991)

|

|

111†† Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus)

by Shirō Kasamatsu, 275 mm x 405 mm, woodblock print

|

|

|

|

|

112†† Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by

Kaoru Kawano, 430 mm x 285 mm, woodblock prints

|

|

|

|

|

(4) Cranes (Gruidae)

The red-crowned crane

continued to be a popular choice for bird prints, appearing in more than

one hundred and fifty prints made by gendai artists. Cranes are

particularly impressive with their wings fully extended in flight, as shown

in print 113.

|

|

113 Red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis)

by Takeo Honma, 380 mm x 270 mm, screenprint entitled dawn

|

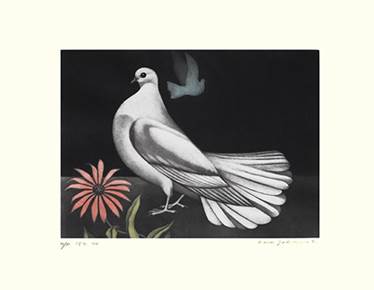

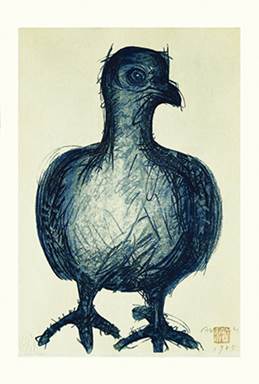

(5) Doves (Columbidae)

The dovea was

another domesticated bird species favored by gendai artists. Introduced to

Japan from Europe, it comes in a variety of shapes, sizes and colors thanks

to selective breeding by humans. The pure white form shown in print 114 is

particularly attractive and was chosen most often by gendai artists.†

a†† Also called pigeon. There is no clear

difference between birds called doves versus pigeons.††

|

|

114†† Dove (Columba livia) by

Kōichi Sakamoto, 350 mm x 270 mm, intaglio print entitled the two

standing

|

†

|

†††† About a third

(38%) of the species chosen by gendai artists did not appear in either

shin hanga or ukiyo-e bird prints. Gendai artists were likely familiara

with more foreign birds which accounted for almost half (41%) of the

species unique to gendai bird prints. Prints 115 and 116 show two of

these unique foreign birdsb.† An artistís personal preferences

likely affected his or her choice of species and because the number of

gendai artists who made bird prints was far greater than the number of

shin hanga or ukiyo-e bird artists. Gendai artists were bound to select

some new native species as wellc.

†

a†† This familiarity most likely came from

direct experience (e.g. international travel) or from new forms of

information technology not available to either shin hanga or ukiyo-e

artists (e.g. television, internet).

b†† Prints 98, 106, 159 and 212 show additional

examples of foreign birds unique to gendai bird prints.

c†† Some examples of native species unique

to gendai bird prints are shown on prints† 103, 111, 138, 166, 195 and

196

|

|

115†† Hermit hummingbird (Phaethornis

sp.) by Shigeki Kuroda, 180 mm x 215 mm, intaglio print entitled

hummingbird and white flowers

|

|

|

116†† Greater flamingo (Phoenicopteros

ruber) by Kazuhiko Sanmonji, 540 mm x 365 mm, woodblock print

entitled blueshore

|

Accuracy of Depiction

The level of accuracy

used by gendai artists to draw birds ranged from (1) inaccurate (46%) to

(2) semi-accurate (35%) or (3) accurate (19%).† Each of these three levels

of accuracy is considered, in turn, below.

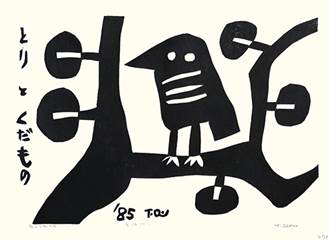

(1) Inaccurate

Some gendai artists

purposely simplified the shapes and (or) colors of their bird subjects to

the extent that it was not possible to recognize even the bird family to

which they belonged. Print 117 is one example. Other artists drew birds

with shapes characteristic of particular families but used too few colors

to allow the bird to be identified at the species level. For example, in

print 118 the birds clearly belong to the gull family (Laridae) but they

lack the bill and leg colors needed to identify the species. Presumably the

goal of gendai artists who drew birds inaccurately (i.e., species not

recognizable) was to be creative and express themselves in a novel way.

This philosophy of art was the hallmark of modern western art whose style a

number of Japanese artists adopted with vigor for bird prints after World War

II. Before then Japanese bird print artists had used a style influenced by

either western realistic art (i.e., shin hanga artists) or Chinese art

(i.e., ukiyo-e artists). Consequently, less than 1% of the bird species in

their prints are unidentifiable. †

|

|

117†† Unidentified bird by Takeji Asano, 400

mm x 295 mm, woodblock print entitled bird and fruit

|

|

|

118†† Gull (Larus sp.) by Shigeyuki

Ōhashi, 375 mm x 280 mm, screenprint entitled migration two

|

(2) Semi-accurate

In some gendai prints

the bird species was identifiable but its shape or color was not completely

true-to-life (i.e., semi-accurate). For example, in print 119 only the

shape and color of the crest of the pair of domestic fowl was accurate. In

print 120 the shape of the little ringed plover was accurate enough for

viewers to identify it but its true colors were reduced to black and white.

These two gendai bird prints are similar to ukiyo-e bird prints in which

the shapes and colors of birds were also drawn only semi-accurately.

|

|

119†† Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by

Taeko Takabe, 270 mm x 265 mm, screenprint

|

|

|

120†† Little ringed plover (Charadrius

dubius) by Gyōjin Murakami, 485 x 330 mm, woodblock print

entitled shore plover

|

(3) Accurate

A minority of gendai

artists drew birds accurately (i.e., true-to-life shape and color). These

artists tended to use either intaglio or digital printmaking methodsa

which allowed the fine details of a birdís external features to be shown

more easily than in woodblock printing. The intaglio print 121 and digital

print 122 below are excellent examples of the high level of accuracy

achievable using these printmaking methods. Presumably these gendai artists

sought to be creative and novel by drawing birds more accurately, instead

of less accurately, than either shin hanga or ukiyo-e artists.†

a†† These methods are explained in the next

section.

|

121a†† Domestic goose (Anser cygnoides)

by Mikio Watanabe, 300 mm x 250 mm, intaglio print entitled goose I

|

|

121b†† Enlargement of the domestic goose in

print 121a

|

|

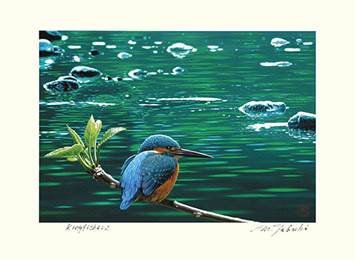

122a†† Common kingfisher (Alcedo atthis)

by Masahiro Tabuki, 320 mm x 235 mm, digital print entitled kingfishers

|

122b†† Enlargement of the common kingfisher in

print 122a

|

Methods of

Printmaking

Five different methods

of printmaking were used to produce gendai bird prints; namely, (1)

woodblock (47%), (2) intaglio (26%), (3) screen and stencil (13%), (4)

lithograph (10%) and (5) digital (4%). Each of these five methods is

described belowa using examples of gendai bird prints.

a†† For additional information about

printmaking techniques see Saff and Sacilotto† (1978).

(1) Woodblock

The Japanese method of

woodblock printmaking which had been used to produce all ukiyo-e and shin

hanga bird prints was also employed most often by gendai artists to make

their bird prints. Typically the woodblock was a piece of wood cut

longitudinally from the stem of a tree. However, some gendai artists used

either wood veneer (i.e., plywood) or pieces of wood cut in cross section

instead. Plywood was a modern western invention which had two advantages

over longitudinally-cut woodblocks. First, it was cheaper and second, it

was available in larger sizes which allowed gendai printmakers to make much

larger prints than their shin hanga and ukiyo-e predecessors. For example,

print 123 is more than double the size of the largest shin hanga or ukiyo-e

bird print.†

|

123†† Whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) by

Fumio Kitaoka, 925 mm x 635 mm, woodblock print entitled swans on

icefield

|

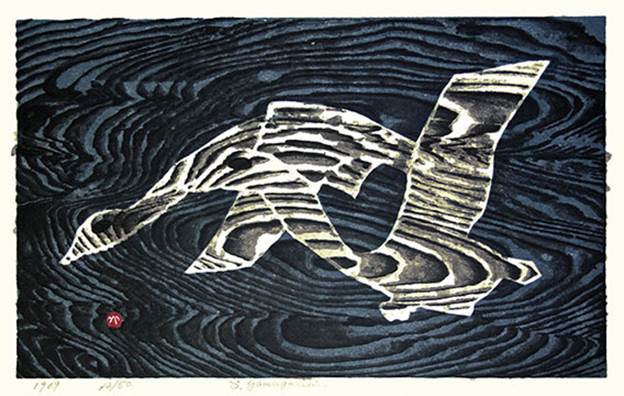

The woodís grain was very obvious on some pieces

of plywood and gendai artists used this pronounced grain to enhance the

sense of movement in prints where active birds where depicted. Print 124 is

one example.

|

124†† Duck (Anas sp.) by Susumu

Yamaguchi, 585 mm x 370 mm, woodblock print

|

|

†††† A few gendai printmakers adopted the western

practice of carving designs on a cross section of wood instead of a

longitudinally-cut piece of wood. The surface of a cross section was

harder which allowed more prints to be produced. However, its greater

strength made it more difficult to carve and special tools used by metal

engravers were required for carving. In addition, the size of prints was

limited because tree stem diameter (i.e., cross section) was much less than

stem height (i.e., longitudinal). Wood engraved prints were typically

round (i.e., cross section) instead of square (i.e., longitudinal). Print

125 is an example of a gendai, wood-engraved bird print.

|

|

125 ††Ural owl (Strix uralensis) by

Kōhō Ōuchi, 180 mm x 180 mm, wood engraved print entitled

blooming

|

(2) Intaglio

Intaglio is an Italian

word meaning to cut into. In intaglio printmaking the design was cut into a

piece of metal and the cuts were filled with ink. A piece of paper was then

pushed into the cuts using a mechanical press to transfer the ink to paper.

Cuts could be made using a metal tool or acid or both to create different

artistic effects. The four types of intaglio printmaking used most often to

produce gendai bird prints were mezzotint, etching, aquatint and drypoint

engraving. An example of each is described below.

The Italian word

mezzotint means half tone and this method was used to emphasize tonal

variation in the color of the object depicted. To produce a mezzotint the

entire metal plate was first roughen (i.e., cut into) with a metal tool.

Then portions of the plate were smoothed to reduce the depth of cut to

differing degrees. When ink was added the deepest cuts held the most ink

and would print darkest. In print 126 the black background had the deepest

cuts and the whitish shades of the birdís image had the shallowest cuts. If

more than one color of ink was needed, as in print 127, then an additional

metal plate was prepared for each color.

|

126†† Ural owl (Strix uralensis) by

Tadashi Ikai, 195 mm x 225 mm, intaglio print entitled owl A

|

|

127†† Japanese white-eye (Zosterops

japonicus) by Tadashi Ikai, 205 mm x 235 mm, intaglio print entitled

Japanese white-eye C

|

Etching is an

intaglio printing method in which acid was used to create cuts in a metal

plate. First the plate was entirely coated with an acid-resistant

substance. Next, areas to be cut were traced onto the plate to remove

portions of the acid-resistance substance. Then the plate was dipped into

an acid bath to produce the cuts. Prints 128 and 129 are examples of

single-color and multi-color etchings, respectively. These prints show much

less tonal variation than the mezzotints above. Greater tonal variation

could be achieved if the acid-resistant substance was sprayed onto the

metal plate to provide only partial coverage. The term aquatint is used

instead of etching when the plate was sprayed instead of coated. In print

130 this aquatint technique was used to depict the tree leaves at the top

of the print. The black lines in print 130 were drawn using drypoint

engraving. In drypoint engraving a sharp needle (i.e., dry point) was used

to cut the lines of the design into a metal plate. The black lines in print

131 were also produced using drypoint engraving while the areas of red,

yellow and blue color were created by etching.†††††††††

|

|

128†† Dusky thrush (Turdus naumanni) by

Takeshi Nakai, 135 mm x 115 mm, intaglio print

|

|

|

|

|

129†† Eurasian eagle owl (Bubo bubo) by

Tomiko Matsuno, 195 mm x 195 mm, intaglio print

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

130†† Domestic goose (Anser cygnoides)

by Kenji Ushiku, 315 mm x 495 mm, intaglio print entitled in the forest Y

|

|

131†† Unidentified bird by Masuo Ikeda, 285 mm

x 380 mm, intaglio print entitled happy bird

|

(3) Screen and stencil

|

In this method of

printmaking a template of the design was first made using either a screen

or a stencil. The screen template was typically a piece of mesh fabric

(e.g., silk, polyester), or less often a piece of porous paper, which was

covered with a non-porous substance except in areas of the design. The

stencil template was usually a piece of stiff paper into which holes were

cut to reveal the design. To make a print the template was placed on top

of a piece of paper and ink was applied. The ink only passed through

areas of the screen not covered by the non-porous substance or through

holes in the stencil to reproduce the design on the paper below. For

multi-colored prints multiple templates were made, one for each color.

For almost all gendai bird prints a screen was used instead of a stencil.

Mesh screenprints (e.g., print 132) often featured strongly graded colora

while color was applied more uniformly on paper screenprints (e.g.,

print 133). Print 134 is one of the very few gendai stencil bird prints.

a†† Strongly graded color was produced by

placing ink at one end of the mesh screen and drawing it to the other end

of the screen using a squeegee. The color became progressively lightly as

the quantity of ink decreased.

|

|

132†† Dove (Columba sp.) by Kōzō

Inoue, 120 mm x 170 mm, screenprint

|

|

133†† Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus)

by Hiroshi Kabe, 195 mm x 270 mm, screenprint entitled two

|

|

134†† Domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) by

Sadao Watanabe, 225 mm x 330 mm, stencil print

|

(4) Lithograph

To make a lithograph the

design was first drawn on the surface of a smooth slab of limestonea

using a greasy substance that would readily absorb ink. Ink was then added

and a piece of paper was placed on top of the inked surface. Finally,

pressure was applied using a mechanical press to transfer the ink to paper.

To make a multi-colored print this process was repeated using a different

stone slab for each ink color. Gendai artists made about equal numbers of

single-color lithographs (print 135) and multi-color lithographs (prints

136, 137) featuring birds.

a†† A light-weight aluminum plate was

sometimes used instead of a heavy limestone slab.

|

|

135†† Unidentified bird† by Kiyoshi Awazu, 280

mm x 415 mm, lithograph entitled blue bird

|

|

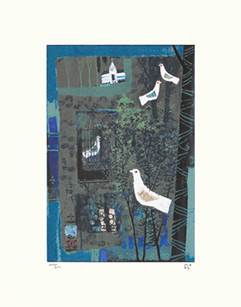

136†† Dove (Columba sp.) by Gikō

Hayakawa, 260 mm x 330 mm, lithograph entitled in the green forest

|

|

|

137†† Hummingbird (Family Trochilidae) by

Shōmei Yoh, 500 mm x 260 mm, lithograph entitled the elephantís

dream garden

|

(5) Digital

|

In digital printmaking

the design was first created using a drawing program that was written for

the digital computer. This design was then sent electronically to a

mechanical printing device which made a paper copy of the digital design

by adding ink to paper.

†††† Digital

printmakers depicted birds in two very different ways. Some drew birds

very accurately as in print 138. Others combined their imagination with

the power of digital technology to create novel images of birds. For

example, in print 139 the birdís feather pattern was simplified and the

color of each feather was graded so strongly that it looks more three

dimensional than in true life.

a†† Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator

were the two drawing programs used most often to produce digital, gendai

bird prints.

|

|

138†† Water pipit (Anthus spinoletta)

by Masahiro Tabuki, 330 mm x 485 mm, digital print

|

|

|

|

|

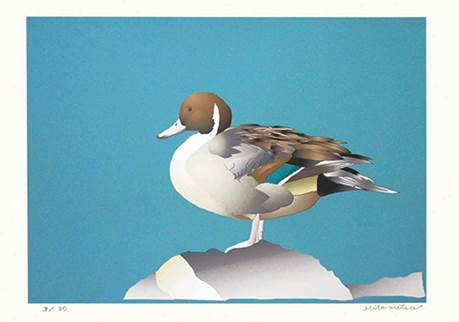

139†† Northern pintail duck (Anas acuta)

by Hiromitsu Sakai, 425 mm x 295 mm, digital print

|

|

214a††

Gray wagtail (Motacilla cinerea) by Akira Fujie, 375 mm x 265 mm,

intaglio print entitled wagtail

|

214b††

Enlargement of the picture portion of print 214a

|

|